Home Fire, Kamila Shamsie

September 14, 2017 § 4 Comments

This is a hard book to review. I wanted to love it but I have some significant issues. In a sense, this is a timely reworking of Antigone.This novel considers present-day issues of state power, borders, and terrorism. The ideas are worth thinking about but I feel the depth of the novel is less a feature of its writing, structure, characters, and plot, and more about what present-day readers will bring to their reading of the book. It’s the fact that it’s about our current political and social issues and the fact that it’s based on Antigone. I’ve seen reviews where people say they would have given it two stars, but knowing that it was based on Antigone elevated the book to three stars. I’m not sure that this reflects well on the novel.

Some of my issues: (SPOILERS AHEAD)

Antigone as the novel’s symbolic framework is also its limitation. I have a significant problem with the romance and the blockbuster film ending, and I can see it had to work that way to fit the parameters of the tragedy on which it’s based. But it simply did not feel true. This is largely in part to the flimsiness of the central characters of Aneeka (Antigone) and Eamonn (Haemon). Aneeka comes off as a cardboard character of a moody girl who’s mysterious in her ways and beautiful and unpredictable and impulsive, while Eamonn is a shell of supposed charm and humour and earnest do-gooder privilege. So far, so stereotypical. Much of the gravitas of Antigone is lost because Aneeka is not given the depth of a narrative voice. We see her through others. To Eamonn, she appears as some Manic Pixie Muslim Dream Girl. Their sudden passion and attraction does not leap off the pages. Maybe part of this is because Aneeka had a motive for getting closer to Eamonn, and Shamsie wanted to convey the “is it real or is it not” ambivalence of the romance. Or whatever. I did not care at all and that to me is a significant flaw. I was rolling my eyes and writing “Oh, please” in the margins. The wheels of this story is set in motion by their love. It felt like a weird, coldly-choreographed infatuation.

There is this really cringe-worthy scene after they have sex, when Eamonn looks at Aneeka praying after she has naughtily taken off everything for him except her hijab. Eamonn is the cultured, cosmopolitan posh Muslim boy who has, thanks to how he was raised, disavowed his Muslim self, but as it turns out what really turns him on is hijab sex with a hot hijabi! This is the section from his perspective: “He should have left immediately, but he couldn’t help watching this woman, this stranger, prostrating herself to God in the room where she had been down on her knees for a very different purpose just hours earlier”. Oooh. First she was down on her knees for dirty times and now she’s down on her knees for God! Honestly, I thought this self-Orientalising nonsense was Shamsie’s way of poking fun at Eamonn’s privileged worldview and insularity, but Eamonn is only depicted in such a tediously dull way as a Good Man that it turns out that scene was quite sincere.

Isma (Ismene) and Karamat (Creon), and even Parvaiz (Polyneices) to an extent, are complex and dynamic. Isma is the heart of the story but she is made to have a supporting role, because this novel needs to construct itself around the Antigone tragedy. The connection between Isma and Karamat could have developed into something interesting but that was prevented because, again, Antigone. I’d rather read a whole novel about Isma and Karamat. But Aneeka? Repeated references to her beauty does not a character make.

Despite enjoying the sections on Isma and Karamat, and feeling moved by Parvaiz’s situation, or rather, by the burden of family and fate that he feels he shoulders in isolation, I failed to connect to the novel as whole. Ultimately, it’s too comfortably bourgeois, too careful and too centrist in its politics. Shamsie’s language is polished and careful. Sometimes this language is a delight to read; it slips down easily and comfortingly like pudding, but sometimes it veers lazily towards sentimental platitude. Not having read Shamsie before, I’m not sure if this is her style. I know what the politics were going to be and I know that it’s meant to pull the right emotional strings. It’s meant to make you feel bad about good, innocent Muslims vs. the very evil and bad ones.This is not because I know what happens in Sophocles’ tragedy. This is because there is nothing remotely unpredictable in here that I haven’t read in zillions of liberal op-eds and thinkpieces.

Where is the ugliness, the blood, the mess, the absolute and mind-numbing fear and uncertainty brought on by the bureaucracy of borders and the security state? These characters move around like pieces on a chessboard. I can accept this if the novel was brave enough to take fate as a serious concept like the ancients did. Because part of that utter futility of human effort is at the centre of ancient Greek thought and in Sophocles’ play. The terror and awe of Antigone’s commitment to the gods and the concept of philia. But we live in a different time and we’re all materialists now even if we’re not, and this novel wants to be a realist novel of action, of cause and effect, and everything is so self-contained.

Aneeka’s love for Parvaiz and her willingness to do anything to get him buried at home is utterly unreasonable to others because she’s one half of twins. Great. So it basically comes down to: she’s acting that way because, well, twins! You know how they are!

What about Aneeka’s God and how she wrestles with religion in modern-day, increasingly right-wing UK where the only way “others” are told they should exist is by assimilating? We get a strong, almost sympathetic depiction of that conservative viewpoint via Karamat. In fact, his perspective closes the book. He gets the final word, even if it’s meant to be a representation of his hubris before his personal fall. But there is no real, strong political opposition to his view by other Isma or Aneeka. Isma’s critique of both the police state and Islamophobia carries more weight than Aneeka’s sense of justice. There is never that confrontation between Aneeka and Karamat that enables readers to think of another way of how the state should exist, of a way that it can protect and yes, care for its citizens without trying to eradicate difference in people by means of weapons, war, incarceration, poverty, torture, and weaponised security.

And if this is Antigone, then it’s Aneeka’s impassioned arguments that should strike the heart of the reader. But we only get inside her head at the worst point of her grief, and her viewpoint is submerged in the “chorus” of newspaper reports, tweets, etc. I don’t understand why this section was done this way. It doesn’t work as a structural choice, it doesn’t work as a stylistic choice. Thus, instead of the argument between Karamat and a worthy foe of opposing political views, we are meant to make do with sentimental claptrap about Karamat having to be a father and pleas for him to “be human” from both his wife and son. Really? Both Islamic State fighters and war-mongering NATO politicians think they have the monopoly on what it means to be human, don’t they?

I thought Shamsie was going to take a risk in the Parvaiz section, which I found moving until it was again clinically-engineered by the hand of the author. After giving us an engaging, even sympathetic Parvaiz, I thought Shamsie was going to show us how unreasonable we are in our desires, how mad we can become when faced with a family legacy that is riven with trauma, in a world that is brutal and unjust. That after getting the reader to sympathise with Parvaiz, she would leave him there, with the choice he made, thereby making the reader flail in the uncomfortable space of finding themselves sympathising with a terrorist. Or not sympathising, as such, but living in his head and seeing the world from his eyes. But no. Very quickly Parvaiz repents, and enters the world of good humans again. The dichotomy of Muslims terrorists as monsters and the rest of us as good humans remains. This is straight out of Mahmood Mamdani’s Good Muslim, Bad Muslim, but not in a good way. In fact, it is just like any depiction of “Muslim terrorists” we see in the media. But fiction is not corporate-sponsored journalism. One hopes that if you’re going to write about this, you would take the risk of humanising the people that the media have Othered and made monstrous. Because that is the black hole of our collective consciousness, isn’t it? How is it that people, actual humans, vast numbers of them, think that so many of us are not fit to exist on this planet with them? Shamsie does this by taking an ethical shortcut. Parvaiz regrets his choices; hence, we are allowed to feel pain that he is denied humanity in his death.

Daniel Mendelsohn on Tamerlan Tsarnaev and Antigone’s relevance: “This is the point that obsessed Sophocles’ Antigone: that to not bury her brother, to not treat the war criminal like a human being, would ultimately have been to forfeit her own humanity. This is why it was worth dying for.” There is none of this terrifying, heart-rending power of sticking to a principle, of ethics, conveyed in Aneeka’s position. This to me would have been the most crucial aspect of the novel, the element that should have been carefully developed, the bright flame at its core. I searched for it and was left wanting.

To me, all of this suggests that the reader is meant to fill in the gaps in Shamsie’s book by connecting it to the long, rich history of interpretations and readings of Antigone. Instead of fleshing out a key character in the novel and the mechanics of its plot, we are meant to assume Aneeka’s actions are powerful and tragic based on what we know about the tragedy. Such a shame. There are seeds in here for a novel that could have been really messy, brave, and complex. I was expecting so much! I still think it’s worth reading, despite my lengthy criticism, but it’s not memorable and it did not shake me up inside, it did not take my thinking to new places. It’s worth reading because it’s topical and relevant. But it could have been so much more.

Hanif Kureishi”s The Nothing

July 14, 2017 § Leave a comment

My review of Hanif Kureishi’s The Nothing appeared in The Star last week. It’s available here.

This is the review in full:

In Hanif Kureishi’s brief and caustic novella The Nothing, Waldo is a celebrated filmmaker who is confined to his apartment because of illness and advancing age. He has lately begun to suspect that his wife Zee, younger by twenty-two years, has begun an affair with Eddie, “more than an acquaintance and less than a friend for over thirty years”. This is the story of Waldo’s descent into paranoia, obsession, and sexual jealousy.

Eddie is a scamp, an itinerant shifty dude who has done some film journalism and written about Waldo. Currently, because of money troubles, he is largely living with Waldo and Zee on the pretext of assisting Zee with caring for Waldo. And care for Waldo he does; he has even given him a bath. Waldo has tolerated him and enjoyed his company all these years, to an extent, because Eddie has interesting things to say about movies and “adores the famous” and is a “dirty-minded raconteur”. Waldo describes in detail why he tolerates Eddie and keeps him around, but his exact words are not fit to be printed in this venue.

It is that kind of a book. It’s always a pleasure to read Kureishi, and this is shot through with vivid descriptions and black humour on every page. It’s obnoxious, clever, and bawdy, much like its main character. The whole novel is told from Waldo’s extremely graphic and increasingly paranoid first-person point-of-view. As Waldo says of his detailed, obsessive fantasies, “I like to think I can see it. I was always a camera”. The reader is reminded that “the imagination is the most dangerous place on earth”.

A glimpse into Waldo’s character can be seen in this nugget:

If you’ve once been attractive, desirable, and charismatic, with a good body, you never forget it. Intelligence and effort can be no compensation for ugliness. Beauty is the only thing, it can’t be bought, and the beautiful are the truly entitled. However you end up, you live your whole life as a member of an exclusive club. You never stop pitying the less blessed. Filth like Eddie.

If this makes you want to suffocate him with a pillow, you won’t be the first in line. Certainly his wife is tempted to do the same. But as Waldo reveals more of himself throughout the book, one starts to wonder if all this philosophising is just a cover for a real and actual fear: the slow, creeping realisation by someone on their death bed that all that they hold dear might not be what makes the world go around. If beauty and desirability are the true forms of entitlement and the ugly are to be pitied-from the perspective of someone who has always had both-then what makes an average-looking man like Eddie such a hit with the ladies, including his own wife?

Waldo would certainly bristle if you called him a misogynist; he might counter that he does in fact love women, and would probably privately write you off as a prudish, repressed feminist, which in turn would affirm the fact. That’s the kind of man Waldo is. He does love women, but only if they’re pleasing to his eye and sexually-alluring. If they’re not, they’re dispensed with in one sentence, like Maria, “the kind Brazilian maid”. Waldo’s appreciation for his friend Anita, one of the actresses he has directed, is summed up in an assessment of a physical feature of hers that also cannot be reprinted in this venue.

If you love sharp, snappy writing with a keen sense of rhythm and pacing, this book has it. Waldo’s bon mots are clever and provoking but the whole thing can often feel like one giant quip. And that might be the problem with the book: while Kureishi has established an incredibly vital sense of character through Waldo’s voice, there’s never a sense that anything is truly at stake. The obsession with his wife stays on the surface, though when Waldo tries to contextualise how a rogue like him fell in love with this one deserving woman, it sounds a bit hokey, like something he’s memorised from a Hallmark card.

Thus one isn’t quite sure what was Kureishi’s intention in this character study. Perhaps a man who values looks, charm, sexual allure and glamour like Waldo can always only skate on the surface. As always, one is left wondering about the women whom we have only seen through one man’s eyes. One wants to know more about them and why they are this way. Seen by Waldo, Zee veers from petulant to crazed and fulfills all the stereotypes about attractive women who are constantly threatened by the presence of women who are considered more attractive. Yet she is fascinating; Kureishi gives her some amazing lines.

The book ends abruptly, with a bleak solution. Waldo is no fool and he hasn’t had the wool pulled over his eyes, but things have certainly gone his way-in a sense. Waldo’s voice is memorable and I will probably still think about his pitiful masculine ways for some time. “You have savage eyes”, Zee tells her director husband, and the same could be said of the male gaze in general, as well as of Kureishi. Whether or not one enjoys this book depends quite a bit on how much of this savagery one is willing to sit through.

Anuk Arudpragasam’s The Story of a Brief Marriage

June 28, 2017 § Leave a comment

I reviewed Anuk Arudpragasam’s The Story of a Brief Marriage for PopMatters. Here is an excerpt from the review:

It seems wrong, somehow, that some reviewers on Goodreads and elsewhere have pointed out that this novel is too thoughtful and does not teach the readers about the war in Sri Lanka or give detailed descriptions of what one expects to be the correct image of a refugee in a war camp. Writers of fiction are not obliged to teach the reader anything; novels are an act of imagination that ideally should spur the reader to learn more about the social and political contexts in which it’s set on their own. To say that a thoughtful and introspective, reflective tone is an inaccurate description of a person in the midst of war also reveals a limited and perhaps even condescending worldview; one that assumes that people in dire straits somehow continually exist in a state of animal-like barbarity that precludes thinking and feeling in ways that the reader might recognise. There is a need, on the part of the well-adjusted reader reading about the horrors of life from a position of relative comfort, for a certain degree of suffering that they can pass judgment on and deem sufficient; it enables them to give themselves, as readers of harrowing things, a pat on the back.

Arudpragasam has bypassed the usual conventions of writing about war. This book is small in scope, distilled into the course of one day featuring a single and singular point-of-view. This is a novel of integrity, in the sense that Virginia Woolf refers to in A Room of One’s Own: “What one means by integrity, in the case of the novelist, is the conviction that he gives one that this is the truth. Yes, one feels, I should never have thought that this could be so; I have never known people behaving like that. But you have convinced me that so it is, so it happens.” This book affords its characters, especially the central character through whom we see this slice of war-ravaged world, dignity.

The full review is available here.

the white room

May 28, 2017 § Leave a comment

Joanna Walsh’s Vertigo is a glacial collection of stories that are admirable in their intelligence, coolness, and reserve. These are minimalist, tidy, self-contained stories, and while they are worth reading for the writing and the style, they were not capacious or generous. I felt like I had to be really careful, as if I were in someone’s all-white living room without a single smudge of dirt and if I so much as moved I would leave a stain on the white.

After watching Get Out I’ve been thinking a lot about how this works. The interior space and the reproduction of white supremacy, especially in the benevolent form of white liberalism. The interiority of white narrators can sometimes be like a cold, cavernous white room that has no space for the excess and muck of other colours, like brown. (Ha.) If I’m going deep into the consciousness of a narrator, I prefer to see the mess and the ugliness. The grotesque. Maybe that’s just me.

And so while I admired this book, I did not love it. But I’m beginning to understand why white women who write like this are critically adored and praised. It’s a version of feminine cool that leaves the hysteria and the excessive feeling at the door. To be excessive is to demonstrate one’s lack of power. The anger and the rage that so many brown people, in particular, are accused of exhibiting are absent or subsumed into a more pleasing form, one that whispers elegantly: this is Literature for the intelligent. This is an aesthetically-pleasing form, much like the Instagram feeds of financially-secure people in the first world.

I think about Kathleen Collins’ Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?, a book that really gave me vertigo, and I say that as a compliment. Throughout the title story, set in the 1960s, which Collins tells us with a sharp dose of irony, is “the year of the human being”, she differentiates her characters with the pointed use of descriptors in quotation marks: “white”, “negro”. This is the main character (“negro”) in the story:

I insisted loudly that she shoes were in bad taste and the lipstick was too gaudy because I didn’t wear shoes like that just because I was colored and couldn’t he tell I didn’t give off any odor of any kind just because I was colored and that I always held my breath every time I went into his store because I was colored and didn’t want to give off any odor of any kind so I tightened my stomach muscles and stopped breathing and that way I knew nothing unpleasant would escape — not a thought nor an odor nor an ungrammatical sentence nor bad posture nor halitosis nor pimples because I was sucking in my stomach and holding it while I tried on his shoes and couldn’t he see that I was one of those colored people who had taste.

This is how it feels to sometimes inhabit the space of white writing, the kind of white writing critically-praised by Serious White People Who Love Literature, like I’m holding my breath and trying to not give off any odor while I try to show the Serious White People Who Love Literature that I have taste, so I hem and haw about why I did not love the pristine white book that they love.

Brookner: Anger of the Underdog

February 20, 2017 § Leave a comment

I have not read this but I should be preparing myself, if this quote is any indication. I’ve only read one Brookner novel, A Start in Life, and felt that to read any more required some preparation on my part, for the quiet passages and the quiet devastation they bring on, like this one.

Reputations by Juan Gabriel Vásquez

February 7, 2017 § Leave a comment

An excerpt of my review of Juan Gabriel Vásquez’s novel, Reputations. The full review is available here:

Reputations is the sixth novel by Colombian writer Juan Gabriel Vásquez, though his Wikipedia entry explains that he has only written four “official” novels and would like to forget the existence of the two earlier novels written in his 20s. All four of his official novels have been translated from the Spanish by Anne McLean, who also did the translation for this novel. Vásquez’s previous novels have done well among English-speakers, particularly The Sound of Things Falling, which went on to win the 2014 International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. Reputations, however, is my first exposure to Vásquez.

At just under 200 pages, Reputations is a slim, taut, nervy novel that tells the story of a great man, the reputation he has come to enjoy in his position as a great man, and the slow unravelling of his self-conception after a chance meeting with a young woman. Set in an elegant three-act structure, the first section lays down the groundwork for the character, Javier Mallarino who, when we meet him, is 65 years old and having his shoes shined on a street in Bogotá ahead of an event which will honour his work as a political cartoonist.

The irony of his anti-establishment cartoons being lauded by the establishment is not lost on Mallarino who, despite his greatness and his reputation cemented by the position of his cartoons “in the very center of the first page of opinion columns, that mythic place where Colombians go to hate their public figures or find out why they love them, that great collective couch of a persistently sick country”, goes unrecognised by the person shining his shoes. In that moment of non-recognition, Mallarino also has a moment of misrecognition—in his case, he thinks he sees the figure of the “greatest political cartoonist in Colombian history”, Ricardo Rendón, walk past him on the street “despite having been dead for seventy-nine years”.

The death of the political cartoonist is a foreshadowing of what happens later in the novel, in the metaphorical sense of a social death, and how people continue to live on in the public imagination. After a fluidly-written first part that builds up Mallarino’s life and his ascent into his current status, a younger 30-something woman named Samanta Leal approaches him at the ceremony, introduces herself as a journalist, and comes up to his house in the mountains the next morning to interview him. Mallarino “liked the idea of living up at those altitudes and frequently used it to impress the gullible, even if it was an exaggeration: my house is in the Bogotá highlands”.

That Mallarino likes being above it all is one of the small, discreet clues about his character that foreshadows the revelation that comes in the second part. Up until the current point, the reader has gone along with the pleasing, seductive, wry voice of the narrative that has revealed Mallarino’s life with entertaining nuggets of anecdotes and events. We slowly learn that Mallarino moved into this house after his wife Magdalena split up with him, as she found it difficult to recognise the man she loved in this new public figure who is admired and praised by the intellectual class. It’s tough to love a Great Man, much less live with him, and behind every one there is a woman who has been privy to the deterioration of his original values and character. But when Mallarino tells his story to Samanta, he says he moved into this house simply because he “got tired of Bogotá”. It gives us a glimpse of Mallarino as someone invested in his own self-image as a person far removed from the petty concerns of the materialistic population of the crowded city.

Bye Bye Blondie by Virginie Despentes

January 22, 2017 § Leave a comment

I don’t have goals or resolutions, which probably explains a lot about my life, but I do have an idea of what I want to do more of in 2017, and part of that is more writing here and less opinions on Twitter. So far I’ve managed to stay off Twitter but I can’t get back into the rhythm of blogging, for some reason. But we’ll see how it goes. I’ve been very bad about updating the blog with reviews and writings I’ve done elsewhere, and for the last year or so I’ve done a lot of reviews but I haven’t really highlighted it here. I’ll try to get back on track with that, just because I do spend a lot of time working on the reviews, and even if the world is ending I still like engaging with the thoughts and ideas of another mind that one can encounter in books. So here’s an excerpt of a review of Virginie Despentes’s Bye Bye Blondie which you can read in full at Full Stop:

Virginie Despentes’ 2010 feminist polemic, King Kong Theory, was a bit like drinking a bitter, black potion steeped in rage and fury concocted by a kind but brutally frank fairy witchmother. “I am writing as an ugly one for the ugly ones: the old hags, the dykes, the frigid, the unfucked, the unfuckables, the neurotics, the psychos, for all those girls who don’t get a look in the universal market of the consumable chick,” Despentes wrote, delivering a manifesto for women who felt alienated and cast-out from the rhetoric of liberal feminism and its framing of gender equality via the spectacle of consumer and celebrity culture. The female protagonist in Despentes’ most recent novel to be translated into English, Bye Bye Blondie, is also one of the girls who don’t get a look in the universal market of the consumable chick. Gloria is getting older and angrier, and the novel is a narrative of that rage and its specificity rooted in Gloria’s position as a working-class woman in France. Published by The Feminist Press and translated from French by Siân Reynolds, Bye Bye Blondie is a blistering account of a woman’s attempt to exist as a person in a capitalist, spectacle-driven, misogynist society while also trying to honor her love for a man and the deep connection she shares with him. Like Chris Kraus in I Love Dick, in this book Despentes too seems to have set out to solve the problem of heterosexuality.

Brief thoughts on Interchange

December 16, 2016 § Leave a comment

I found Interchange to be a mess as some people have said, but a beautiful and intriguing mess. Certain fantasy/memory sequences are so arresting and I can’t stop thinking about it.

(I don’t think there are “spoilers” here, but it’s a film that unspools slowly and requires that you get on board with fragments of information, so I don’t know if reading some of this will spoil the experience if you haven’t watched it. It might.)

I found the “why” of it illogical. That illogic is what enables the film to perpetuate orientalist cliches of Borneo people and what the film deems to be tribal rituals. This is the part that is most incoherent, and leaves me conflicted. The premise is that colonial anthropology and its invasive and harmful mode of study, which required photography as a technology to document, was harmful to the native populations it attempted to “decipher” for the urban, mostly white intellectual class. (Actually, this might not be the premise and this might be me reading too much into the “clues”.) But in the movie, they dropped the ball. If the film went deeper into exploring the effects of colonialism and capitalist modernity, it would have to sacrifice the exotifying gaze that drives the mystery. And this film is like a fantasy, a dream. It’s like Dain Said threw a bunch of stuff in the blender: animism, indigenous spirituality, ecocide, colonialism, magic, enchantment, noir, police procedural, photography, murder mystery, and hoped for a really good sambal to come out of it. It was tasty; I might even go for seconds. But it leaves you with a stomach ache. And then you’re left trying to figure out exactly what went wrong with the sambal.

It’s a visually-stunning film and in its flaws there are things that lodge themselves in the mind. The mingling of the accents, for example. (Several actors are Indonesian and their accent reflects this in the parts where Malay is spoken). I liked that, in the sense of alluding to a greater Malay archipelago, the shifting and dissolving of borders.

My favourite part was the jungle/sanctuary amidst concrete urban jungle scene. I loved it; it’s beautiful and haunting. The first time we see it the mysterious Belian just sort of runs from the city into this dark place, filled with trees and then sort of climbs into a tree and disappears. Then we see it from the inside. It made me yearn for the kind of place I’ve only ever dreamed of, maybe visited and never inhabited. It made me yearn for a kind of green I’ve probably never seen in my lifetime, both a real and mythical green place as an idea of home. There is peace there. But this is at odds with what Belian and the other native people have to do to return to that peace. It also reeks uncomfortably of the “noble savage” idea.

The noble savage trope also connects with Said’s inability to do anything with women that is not a cliche. It was there in Bunohan and it’s here, as well. Iva (Prisia Nasution) keeps appearing in several scenes as the alluring, mysterious woman who makes eyes at Iedil Putra’s Adam and sucks on ice cubes while being coy. Later we know her true role but it also traffics in the cliches of the native woman, and has a distinctly West Malaysian idea of how women from the East are like. Sucking on ice cubes and being coy, apparently. It’s for a certain gaze. The gaze is male, as seen from Adam’s voyeuristic practice of photography, and as seen in law enforcement: the people tasked with “figuring things out” are men.

The film of course doesn’t try to dictate who should be blamed for the condition of the people that leads to the murders. But we know history and we know that blame can be assigned to the ones that came with their cameras and their notebooks. So in a film that leaves this possibility “open”, one only feels the same old disappointment about how Malaysians — urban middle-class West Malaysians in particular — choose to ignore and devalue certain parts of our history. I would love to read critiques of the film that approach these problems head-on. I’ve read some reviews where it’s purely about a psychological analysis, with a dash of auteur theory (linking Interchange to Bunohan) which is fine but limited. Because ultimately this film is about ritual murder framed as a mystery, and it leaves the burden of the killings on the native people for whatever flawed reason the movie thinks is sufficient. And that’s quite unpleasant, to me.

(Nicholas Saputra played Belian and his ordinarily recognisable beautiful form shifts and transforms into something else; it’s not just visual, it’s also in his manner, how he inhabits his body, and his body language. It was unnerving and very good, I thought, and took me by surprise for someone I’ve just sort of vaguely known as a pretty face in Indonesia. Having watched this though, I’ll take him in any form. *heart-eyes*)

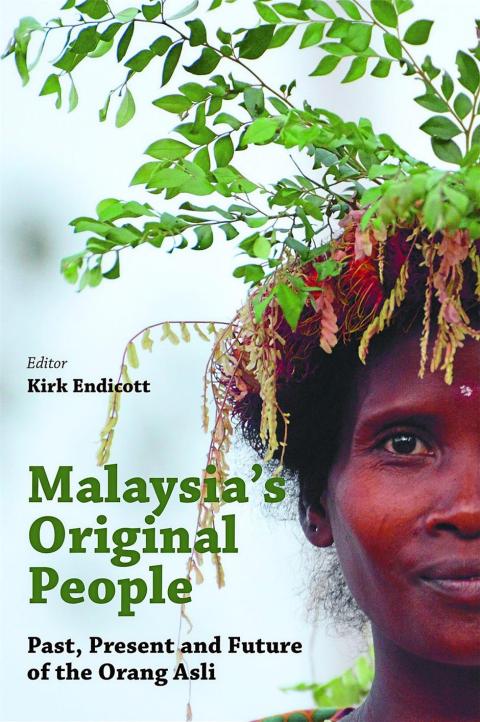

Review of Malaysia’s Original People (ed. Kirk Endicott)

August 16, 2016 § Leave a comment

(A shorter version of this review is in The Star.)

Malaysia’s Original People: Past, Present and Future of the Orang Asli is a dense, far-reaching compendium of essays edited by Kirk Endicott, a professor with the Department of Anthropology at Dartmouth College in the US. His bio states that Endicott has carried out fieldwork with the Batek and various other Orang Asli groups since the 1970s; hence, this anthology naturally features other academics and researchers who have spent many years with the Orang Asli in various capacities. The essays run the gamut from pieces on Orang Asli religion, language, and culture to the legal battles and political situation that renders them displaced and marginalised within the nationalist framework.

Published by the National University of Singapore, the book is systematically divided into several sections under the categories mentioned above. However, as the writers are mostly academics and researchers, each essay is packed with information from several angles; so an essay on Orang Asli animism and cosmology, for instance, is also rife with facts about the history of oppression they’ve faced on the Malay Peninsula, starting from Malay and Indonesian slave raiders of the 18th and 19th centuries. There is no beating around the bush here in an attempt to neutralise or even erase colonial British and Malaysian government complicity in the systematic displacement and marginalisation of the Orang Asli. In fact, this displacement occurs under the guise of “modernisation”; but as Duncan Haladay shows in his essay, “Notes on the Politics and Philosophy in Orang Asli Studies”, around the 1980s, within the rubric of development, the Orang Asli “were subjected to resettlement and pressures toward acculturation, and their sanctuaries were subjected to appropriation and extensive deforestation”. It cites a case study from 1997 that “government policies … appear to be transforming Orang Asli into a demoralized rural lumpenproletariat”. Not the words you’ll see in local media reports on Orang Asli, which, as multiple essays in this book point out, often quote government officials tied to the Jabatan Kemajuan Orang Asli (JAKOA), which is in itself is part of the problem.

Not quoting these words in a review of this book will be intellectually dishonest; from start to finish, these essays excavate the devastating impact of capitalism via the oil plantation and logging industries, for example, and the bureaucratic nature of the capitalist democracies like Malaysia whose state interests are, with greater intensity and frequency, tied to the profits of corporations. As such, states that claim to protect minorities often make decisions in favour of profit and surplus value to the detriment of its people. This is standard anti-capitalist critique; for many Malaysians, however, the ideas might seem new, even ludicrous. We are often encouraged to think of “development” as an abstract idea that is for the greater good, but the Orang Asli were aware of the rampant consumption of resources required for development as a potential ecological and natural disaster from decades ago.

Because it’s written by academics, some essays tend to read as though they were written for other academics and the non-specialist reader might find certain words and terms going over her head. While the essays on Orang Asli religion are fascinating, they are complex and verbose; whole pages were sometimes indecipherable to me because it merely regurgitated a string of words in Orang Asli languages, couched between linguistic concepts, terms, and phrases. Despite these occasional hurdles, these essays demonstrate that Orang Asli beliefs about animism and interconnectedness between humans and non-humans are the key to how they manage the land and resources. It’s not that Orang Asli abstain from eating meat, or clearing land; it’s that they do it within a belief system that says they shouldn’t take more than they should, and that for what is taken, something should be done on the part of humans to restore the balance. As such, blaming indigenous practices of slash-and-burn on the yearly haze, for example, is outright falsification by logging and oil palm companies and stakeholders in order to maintain their image.

Orang Asli practices are managed for the greater good of the community that abhors greed; a key tenet is that one group or family should never have more than the other. They see their biological and spiritual wellbeing as tied to the land and the trees, the rivers, and the wildlife. An interesting concept among most Orang Asli groups is the taboo about mocking or insulting nonhuman life. This is an idea that is almost alien to the money-obsessed, work-driven middle-class urban professionals. To me it demonstrates something beautiful; the value of words and ideas, and the effect it has on one’s own wellbeing and one’s community and family. This interconnectedness makes it hard to close one eye and sanction widespread ecological destruction through various excuses, such as “We need to modernise” or “The technology helps us in the end”. The oil palm industry, on the other hand, is built on profit and works within a system that rewards people who gain more at the expense of others. Whose practices do you think is destructive to the environment?

Another key point is the practice of nonviolence among the Orang Asli; researchers who have lived with them for years explore how it is possible that they never abused their children, or their wives, even when they disagreed. To me, this is astonishing: no child abuse, no rape. These disagreements are always sorted out verbally through intense discussions; and it’s never individualised, as all parties involved must participate. Some speculate that their adherence to non-violence grew out of a reaction to the brutalities faced by the Orang Asli when slave-raiders regularly tore threw the forest to abduct them. Interestingly, a concomitant fact about their practice of non-violence is the communal nature of their societies. Private property doesn’t exist; in the instances where some Orang Asli groups tried to absorb capitalist values and enter into market-based living, earning more at the expense of others, their attitudes changed, and they became selfish. They hoarded what was theirs, which was alien to most Orang Asli. The connection between private property and violence is interesting, here, but as these are anthropologists and not Marxists, it’s not explored in detail.

Malaysia’s Original People is required reading for all Malaysians, but it’s heft and price may be a detriment to some. It’s too bad that such information is not widely available to local readers by local publishers at affordable prices; reading about these issues will engender a seismic shift in most Malaysians’ thinking and our ready acceptance of capitalist values as the best values for competition, innovation, and development. Seen from the point of view of the Orang Asli, however, it looks different. They foresaw the dystopian future most of us are now aware of with regards to climate change from more than a mile away. However, they continue to struggle against oppression against a nationalist framework that valorises them as “the original people” in theory, but in practice, ensures that they remain irrelevant and on the margins, displaced in resettlement villages, and left out of educational opportunities that lead to better-paying jobs. Forced out of the forest by an intricate legal framework that gazettes their ancestral land for “wildlife reserves” (oh, the irony) and development, and forced to assimilate into Malayness (an official “secret” until the 1990s, as Diana Riboli’s essay makes clear), some of the Orang Asli have survived by retreating further back into the forest and refusing the state’s demands to assimilate, convert into another religion, and erase themselves. More Malaysians should learn not to accept what’s being done to them in the name of a so-called developed Malaysia. We, like the Orang Asli, should learn how to say no.

Dirt and the housewife

May 29, 2016 § Leave a comment

A fragmented history of bourgeois morality, sexual division of labour, dirt, and the middle-class housewife via two books excerpted below; Kipnis’s one on North American feminism (broadly speaking) and Theweleit’s one on the rise of white supremacy and fascism in Germany in relation to gender relations and the advent of capitalism.

Laura Kipnis, The Female Thing: Dirt, Envy, Sex, Vulnerability:

Note that the dirt-sex dilemma hasn’t only played out in the nation’s kitchens and bathrooms, it’s left its mark on history as well, and nowhere more conspicuously than in the female social-purity movement of the mid-to-late nineteenth century. The “movement” was actually hundreds of separate organizations and campaigns, with rousing names like the National Vigilance Association and the Moral Reform Union, variously devoted to anti-vice agitation and temperance campaigns, rallying against gambling, prostitution, and general male sexual loucheness. All this first took off in England and the United States, eventually spawning international organizations and world congresses aimed at cleaning up male behavior everywhere. Themes of public hygiene and sanitary reform were tied to morality campaigns, with women undertaking to purify society on all levels, public and private, through legislation, street-corner proselytizing, or whatever it took.

…

In retrospect it make (sic) sense that with the rise of industrialization in the nineteenth century, a compensatory cult of domesticity took hold. The home became a sanctified realm removed from the tawdriness of the marketplace, and it was the new sentimentality about the home that gave the women the platform to assert a new public authority as guardians of national purity. When Frances Willard, founder of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, pronounced that her goal was “to make the whole word houselike,” she was floating a new political ideology: that the strength of the nation was directly connected to the strength of the nation’s households. The problem with dividing the world into these increasingly separate male and female domains was that it wasn’t just paid work that was assigned to the male sphere, it was sexuality as well. On their side of the divide, men got sexual passion; women got cleanup duty. One again, thanks.

…

Consider the psychological effects of the flush toilet alone — goodbye to chamber pots, all your bodily wastes thankfully whisked from sight, now only a vague memory — allowing the ever-pertinent question “You think your shit doesn’t stink?” to the enter the social lexicon. Consider too, the new varieties of class contempt directed at the unwashed: if cleanliness is virtuous and the distribution of cleaning advances invariably begins with the moneyed, obviously rich and poor deserve their respective fates. After all, who’s cleaner?

Klaus Theweleit, Male Fantasies vol. 1: Women, Floods, Bodies, History:

The second characteristic of industrial production is that from the very start, it had the capacity to create specific abundance in the midst of general scarcity: toys and baubles for the rich, fashionwear, and every other kind of garbage imaginable.

…

Working and making love became exercises in dying, only to a limited extent were they still creative, life-affirming processes. Every single commodity a worker produced was a piece of his own death. Every act of lovemaking carries the bodies deeper into a debt of guilt that accumulated toward death.

…

Lovers and workers now produce “dirt” from the moment they start their activities. The citizen of a society that began “placing a cover over piano legs, as a simple precaution,” set about keeping both things at a distance, factories and love (flowings as well as machines).

Is it any wonder with all that “dirt” around that the quality of water changed? The habits of washing and swimming in water, including in rivers and lakes, originated in the eighteenth century, in the context of the bourgeoisie’s “moral superiority” over the absolutist nobility. We need to consider the enormously heightened significance of water, in these attempts to implement hygiene in bourgeois society in relation to the simultaneous social proscription of other wet substances (especially those of the body) and the demotion of these substances to the status of “dirt”. At the same time, the phrase “hygiene as a new form of piety” describes only one aspect of the process.

…

The spring is a kind of natural shower for washing off the “dirt” of society. And showers like that found their way into houses. I’m a little surprised to find that I’ve arrived at the conjecture that plumbing had to be installed in private residences to help carry out the repression of human desires in bourgeois societies. (That repression took the form of gender segregation and sexual repression.)

…

Starting from the kitchen and the bedroom, Cleanliness began its triumphal march throughout the house. White lines, white morals, white tablecloths: an incessant rustling of white (no longer audible, but ever present). With the drying up of the streams in the bedroom, moving through the water pipes that were the heart of any clean kitchen, the image of the Pure Mother (the propaganda about clean interiors in houses and bodies) slowly gained ascendancy within the house. The housewife gradually came to embody whiteness, while her husband despaired or started dreaming about the sexual allure of nonhousewives (image of the ocean). Water, water everywhere, but not a drop to drink.