you can’t hurry love

November 12, 2012 § 54 Comments

I’ve been reading sad books. Books about sad people. While I was reading Suzanne Scanlon’s Promising Young Women (which I reviewed here), I was rereading Two Girls, Fat and Thin by Mary Gaitskill, and at this point in my life I must have reread it five or six times. It’s always a bad idea for me to read this book—I’m always in a funk for a week after, sometimes longer, or perhaps but now it’s just lodged itself somewhere inside me and each time I reread it it’s like lighting a match. Two Girls is about two girls, but it’s also about gender war(s), heterosexuality as violence. Chris Kraus writes about wanting to solve heterosexuality before turning 40 in I Love Dick but I feel like every conversation with single straight women friends over beer is an attempt to solve heterosexuality, and after a few drinks the solution is simple: Drink some more or dance; failing that, overthrow the patriarchy and end heterosexuality (somehow).

But what do I know?

It’s just that when I walk around this city I wonder if it makes sense to talk of the Neoliberal Heterosexual Couple. Gym-toned bodies, “tasteful” dressing (“Keep it classy!”—I fucking hate this fucking ubiquitous phrase), identical cannot-be-arsed-about-anything-except-ourselves faces. The couple that won’t let go of each other’s hands even in a crowded walkway; not so much because they’re so In Love and cannot bear to let each other go, but because they have so much contempt for everyone around them who is not-them; contempt written on their faces. Handholding as a weapon, maybe, handholding as a contemptuous gesture. I mean, not being able to step aside, even for a second, for an elderly lady with her shopping bags. The Couple as a Fuck-You-to-the-World might have been a romantic idea at a certain point in time, or even a form of resistance against the status quo, maybe? But now just a part of the obnoxious status quo.

But what do I know? I am single and bitter. (Maggie Nelson, in Bluets: “I have been trying, for some time now, to find dignity in my loneliness. I have been finding this hard to do.”)

And no doubt dying to get married, as various members of the “older generation” have implied to me over the last year. Not even a question, “Do you want to get married?” No. They just know that you need to get married because if you do not you will rot and die. I bumped into an old acquaintance of my father’s a few days ago, while I was with my sister, and among the things he said to me after not having seen me for close to twenty years (I didn’t even recognise him!) was the ever-reliable, “You should get married and take care of your family.” It was the last bit that puzzled me, this idea that I could not be otherwise taking care of my family if I was not married. But it’s not a puzzle really; Tamil people everywhere are on autopilot when it comes to giving Life Advice to wayward young (and not-so-young) women doing horrible things with their lives like being unmarried, cutting their hair short, and wearing red lipstick. GET MARRIED> MAKE THE BABIES> TAKE CARE OF YOUR FAMILY BY MAKING MORE BABIES> YOUR MOTHER IS WORRIED

Etc.

Overthrow the patriarchy. End matrimony. (I shouted, in my head, while smiling vaguely into the distance while this man gave me free life advice. Oh, the smile, how it makes you fucking complicit.)

Thinking about singleness and marriage, stewing over it, often means that I start thinking about beauty. Because it’s beauty that I’m struggling with at this point in time. That is, I lack it, but this is not news to me; when I say “this point in time”, I mean that at this point in life as I know it, it seems that everything is the exterior, that the image is you, and you are nothing but the image. (This day in Capitalism it was discovered there is no there, there.) Romance is a marketplace, and you are one of the many images on sale, and if you’re not the right image you are, essentially, shit. “Never before has society demanded as much proof of submission to an aesthetic ideal, or as much body modification, to achieve physical femininity,” says Virginie Despentes in King Kong Theory and I’m suspicious of the phrases here—“never before”—“society demanded”—yet this sentence rings with truth, for me, and perhaps for other (cis, straight) women who are single and wanting (yearning? dying for?) a connection with someone else that isn’t predicated on aesthetic ideals, all of us who identify as “normal-looking” or “not beautiful” or whatever-

“What if the self-commodification of individuals is all-encompassing, as the analysis of the job market suggests? What if there is no longer a gap between an internal realm of desires, wants and fantasies and the external presentation of oneself as a sexual being? If the image is the reality?”

“Objectification implies that there is something left over in the subject that resists such a capture, that we might protest if we thought someone was trying to deny such interiority, but it’s not clear that contemporary work allows anyone to have an inner life in the way that we might once have understood it.”

-Nina Power, One Dimensional Woman

What if the outside is all we have left?

When I talk about beauty I don’t know what I’m talking about, particularly if I’m also talking about desire, and I want to talk about beauty without talking about Plato or Kant (I just can’t with Kant), and I know for a fact that desire is a colonised space.

“We speak, act, think, behave, and micro-manage ourselves and others according to the “score” that is the general intellect—in short, the protocols or grammar of capital,” Jonathan Beller reminds us. Love in the Time of Capital. Yes, okay, I tell myself I know how to grasp this intellectually, but the bigger fear is that this is the only way I know how to love: according to the protocols of capital.

“Aren’t simple desires dead yet? Are we still so obsessed with the hegemonic body?”

/

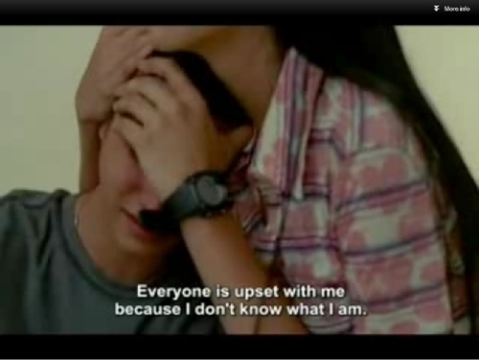

I watched Love of Siam a few weeks ago and cried all the way through it, and after it was over, cried some more, and felt like I couldn’t understand myself—why all these tears? And the movie is a “tear-jerker”, in a sense, in the vein of Asian family dramas that are a blend of realism and melodrama, and so it wasn’t unexpected that a person watching it would cry. But it’s also a film that’s unabashedly pro-love. And as soon as I write that I know it sounds silly—what does it even mean? But I guess it means what it is: it’s a film about love, and not just the “provocative” aspect of young gay love between two Thai adolescent boys that’s highlighted in all the promotional reviews of the film, but also about all the banal and taken-for-granted forms of love between friends and family, the kind that is familiar to me because the families and the communities in Love of Siam remind me a little of what I knew growing up in Malaysia, of how I came to understand the intersection of multiple identities. The differences between these (often conflicting) identities–of discovering one’s queerness, of being a son of an alcoholic, of being a brother, a friend, a grandson, a pop star, a boyfriend—aren’t reified; one identity doesn’t trump the other, and it makes no sense to speak of Love of Siam as a movie only about romantic love or gay love. I contain multitudes, said some American poet and everyone went ooooh, but come on, Asian people have known this forever.

But a big part of this movie is about love between these two boys, Mew and Tong, and it’s the genius of the movie (the result perhaps of the direction and the casting decision to go with two young, relatively inexperienced actors), that the love between these two boys feels so organic and unforced, an entirely surprising yet predictable outcome of shared moments and the pull of desire. Looks are not the currency, eroticism isn’t purchased or a choice[i]; love happens because two people like each other so much, and the question of attraction—sexual or otherwise—is not absent or glossed over so much as it is depicted whole. Mew and Tong are attracted to each other because they’re drawn to each other as people containing multitudes, not because they possess an alluring physicality; not once does anyone tell the other “You’re hot” or “You’re sexy” and I don’t know if I’m regressing or blossoming into full-blown prudedom, but it was so fucking refreshing I don’t even know how to talk about it. I recognise that a lot of the movie’s dialogue and scenes are necessarily circumscribed by the cultural norms in which it was made—in this case, Thai society and Thai censors—but it’s astonishing how much is and was conveyed through looks and faces, and tenderness and understanding. So much of how we understand romance these days is mediated through this narrative of consumerism: “I’m worth it”, “You’re worth it”, “I deserve the best”, “You’re hot”, “I like a nice smile and nice tits”, “I need a man who’s all man, you know what I mean?” All these standards that we think arrive fully-formed in our heads without any external influence, all these principles of picking and choosing The Right One, of having control and autonomy—this movie sort of chips away at those assumptions very quietly and tenderly. The camera loves its subjects; the film loves its characters. The act of loving reveals the love.

But talking about how it’s not a choice doesn’t simply mean that love is something that chooses you. It’s a convenient poetic fiction, and poets and writers and artists talk about it this way all the time, and I fall for the force of that fiction: It wasn’t my choice, I can’t help who I fall in love with. In order for that to happen there has to be an “I” who stands outside of economic, political, social, and cultural influences. So maybe part of my love of Love of Siam is a desire to want to believe in that fiction again. I don’t know though: everything I just wrote down, I believe and don’t believe. Love is attachment, so maybe love is a kind of choice or decision to allow oneself to like/become attracted to a person who is close to you (literally, in the sense that the other person is physically present, as opposed to, say, an image on a dating site; also, figuratively in the sense of a mental and emotional connection based on shared moments, experiences, conversations, and silences that constitute shared time[ii]). Mew and Tong turned inward, toward each other, and it was love. But the movie didn’t require them to turn away from other people, or from life itself. (Although there were necessarily moments where they retreated from life, from people, pulled away and stood aside in order to stand beside each other. But it wasn’t a mode of being, this retreat from life. Their love isn’t about making an investment in coupledom as the only form of solace in a difficult world.)

Similar to the points Elaine Castillo makes about Senna, another movie that moved me in an almost forceful way, Love of Siam is in love with faces—long close-ups of faces dominate throughout. The camera lingers tenderly, lovingly, on faces. I watched it online where the sound and subtitles were off-time; characters would say things before the audio and subtitles kicked in, and although it’s one of the most agonising ways to watch a movie, I kept watching because once I watched the first ten minutes I was hooked. I had to closely watch and observe the faces to understand what was going on before the subtitles arrived to provide the language with which to make sense of these faces. The camera follows their faces slowly and closely, and because the two actors in the lead roles were so young, and almost naïve, watching their faces is a kind of heartbreak. The close-ups of Mew and Tong’s faces are also meant to reveal how much they want to look at each other. The frequency with which they simply look at each other is astonishing; astonishing in the sense that it’s unashamed and assertive. (Here I think about Nicholas Mirzoeff’s The Right to Look, and what it means that two queer Asian boys claim this right so forcefully and tenderly.) I also think about Kelly Oliver’s “The Look of Love”:

“A loving look becomes the inauguration of “subjectivity” without subjects or objects. In Etre Deux, Irigaray suggests that the loving look involves all of the senses and refuses the separation between visible and invisible. A body in love cannot be fixed as an object. The look of love sees the invisible in the visible; both spiritual and carnal, the look of love is of “neither subject nor object”.

Irigaray’s suggestions about the possibility of loving looks turn Sartre’s or Lacan’s anti-social gaze into a look as the circulation of affective psychic energy. The gaze does not have to be a harsh or accusing stare. Rather, affective psychic energy circulates through loving looks. Loving looks nourish and sustain the psyche, the soul, as well as the body. Irigaray’s formulation of the loving look as an alternative to the objectifying look, and her reformulation of recognition beyond domination through love, suggest that the ethical and political power of love can be used to overcome oppression.

There is no happy ending in Love of Siam, though. Nothing is “resolved”. Life goes on and love adjusts its proportions to let life pass through. Love is the vessel and life rushes in to fill it. “If we can love someone so much, how will we be able to handle it one day when we are separated? And if being separated is a part of life, and you know about separation well, is it possible that we can love someone and never be afraid of losing them? Or is it possible that we can live our entire life without loving at all?” Mew asks Tong, and it’s a question that isn’t answered. “Now that we’re grown up, loneliness seems so much worse,” says Mew, and it’s true, and the movie doesn’t rush to fill the loneliness with love. Rather, it suggests that love doesn’t replace that fundamental sense of aloneness, much less transcend it. In the end, Mew and Tong don’t end up together as A Couple, and Tong tells Mew, “I can’t be with you as your boyfriend. But that does not mean I don’t love you.”

/

Maggie Nelson, in Bluets:

238. I want you to know, if you ever read this, there was a time when I would rather have had you by my side than any one of these words; I would rather have had you by my side than all the blue in the world.

239. But now you are talking as if love were a consolation. Simone Weil warned otherwise. “Love is not consolation,” she wrote. “It is light.”

Like when Courtney Love sings in “Malibu”, “I can’t be near you, the light just radiates”.

No happy endings in sight.

/

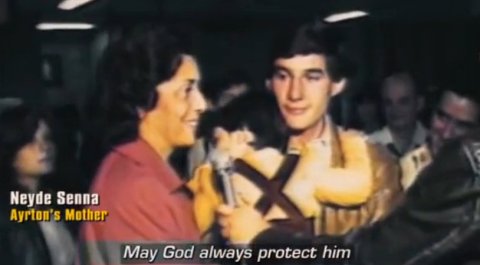

When I think about Senna, too, I think it’s a film about love. It feels like it was made with so much love, and it’s also a movie that’s in love with its subject, a subject who’s not afraid to love his life’s work, the people who matter to him, God. I love that Masha Tupitsyn focuses on what is, for me, the most moving scene in Senna: that brief moment between Senna and his father, which she describes here:

In the scene where Senna wins the Brazilian Grand Prix in 1991 (after he won the race, Senna actually passed out, so great was the anguish of his ecstasy. Victory.), he suffers unbearable shoulder pain from the tremendous stress of the race. He is literally pulled out of the race car and driven off the track. He can barely move. But when Senna sees his father, he calls over to him, “Dad, come here. Come here.” His father hesitates, but Senna insists. “Come here. Come here! Touch me gently,” he orders. His father, much taller, stands beside his son, as Senna rests his head against his father’s chest for a moment. When he starts to walk back, Senna tells everyone else (even before anyone actually touches him; even if no one is trying to touch him at all), “Don’t touch me! Don’t touch me!” He commands everyone but his father to get away from him. This scene, which is the difference between touch me gently and don’t touch me at all, between everyone else and you, between a son and his father, beloved and not-beloved, can also be read as a love story.

If ever a moment could be charged with love, a love so rarely seen on screen in its rawness and vulnerability—the love between father and son—it was this. I think I scrunched my eyes a little when I watched that scene, I wanted to keep looking and then I looked away, mostly because I wanted to cry (tears! again!) because watching felt like I was looking right into a bright light.

Being a witness to love can often feel like an affirmation of something (of what? something you had but lost?), but more often it feels like a wound. Late-capitalist society doesn’t tend wounds; it just looks for ways to avoid it and move on.

[i] There is one scene that involves a kiss. The camera doesn’t intrude; it pulls back, and then goes a little closer, but maintains a respectful distance—this kiss isn’t for the benefit of an audience.

[ii] Which makes me think of this: http://likeafieldmouse.tumblr.com/post/33874562265/felix-gonzalez-torres-perfect-lovers-1987-91 What if lovers are not in-time? “We conquered fate by meeting at a certain TIME in a certain space. We are a product of the time, therefore we give back credit where it is due: time.” And yet—as if it can ever be that simple—“[A]s military time has become militarized time over the past few years, time itself, what is defined as ‘my’ time, has ceased to exist in any meaningful way. We are in the time of service.” How does militarised time shape how we love? What is the neoliberal couple in service of?

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati | Yahoo Buzz | Newsvine